Site Setting and Subsistence: The Local Community, Natural Resources, Prehistoric Climate, and Historic Impacts

By Richard H. Wilshusen

|

Yellow Jacket Canyon at a point close to the Joe Ben Wheat site complex (SL-YJ-185) |

| Joe Ben Wheat Site Complex (Sites 5MT1, 2, and 3) (pdf format) |

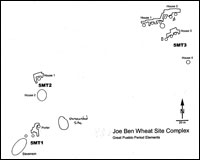

2000 Introduction. Kiva 66:5-18.). They are located on the north side of Yellow Jacket Canyon, approximately 1.2 km downstream from the point where Yellow Jacket Creek becomes an entrenched canyon. The three sites investigated by the University of Colorado Museum's field schools (5MT1, 5MT2, and 5MT3) are separated from Yellow Jacket Pueblo (5MT5), an imposing cluster of masonry roomblocks, towers, road and reservoirs, by a small intermittent drainage named Tatum Draw. 5MT1 and 5MT2 are located very near one another on the crest of a broad, low ridge above the cap rock on the north side of the canyon. Indeed, they are so close to one another (less than 25 meters) that they could easily be classified as a single site. 5MT3, a multi-roomblock site containing at least 50 rooms, is on a small knoll overlooking Tatum Draw, approximately 250 meters to the northeast of 5MT1 and 5MT2.

The setting of the locale must have been among the reasons that made the sites attractive to Joe Ben Wheat when he first started excavating 5MT1 in 1954. The Yellow Jacket sites are within the larger Monument and McElmo drainage unit, which is a very favorable setting for both agriculture and foraging (Adams and Peterson 1999: Table 2-7Adams, Karen R. and Kenneth Lee Petersen

1999 Environment. In Colorado Prehistory: A Context for Southern Colorado Drainage Basin, edited by William D. Lipe, Mark D. Varien, and Richard H. Wilshusen, pp. 14-50. Colorado Council of Professional Archaeologists, Denver.). Although Wheat did not have the details in 1954, it was clear to him that the sites were well placed relative to many natural resources. Additionally, the three sites are only 200 to 500 meters from Yellow Jacket Pueblo (5MT5), the largest ancestral Pueblo site in the Mesa Verde region (Ortman and others 2000:130-131Ortman, Scott G., Donna M. Glowacki, Melissa J. Churchill, and Kristin A. Kuckelman

2000 Pattern and Variation in Northern San Juan Village Histories. Kiva 66:123-146.). Even in the 1950s, Yellow Jacket Pueblo was well recognized as one of the largest prehistoric sites in the whole region. Within several years of initiating the work, Wheat appreciated the possibility that, owing to their favorable location, these sites might have been occupied for a long time and have played a central role in the prehistory of the region. This fit well with his plan to understand prehistoric change in the Mesa Verde region.

By briefly examining the community setting, nearby natural resources, and general pattern of climate change between A.D. 600 and A.D. 1300 we can frame some of the key research issues at these sites and place Wheat's investigations into a broader context. The historic uses of this area are also reviewed, because they are the primary sources of site disturbance in the region. More detailed discussions on the local environmental setting can be found in documents describing Crow Canyon Archaeological Center's recent investigations at Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Kuckelman 2003aKuckelman, Kristin A. (editor)

2003a The Archaeology of Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Site 5MT5): Excavations at a Large Community Center in Southwestern Colorado [HTML Title]. Available: http://www.crowcanyon.org/yellowjacket. Date of use: January 20, 2005.) and in student theses describing the University of Colorado Museum's excavations (e.g., Cater 1989Cater, John D.

1989 Chronological Understanding of Site 5MT2, Yellow Jacket, Colorado, and a Study of Abandonment Modes. Unpublished MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado, Boulder.; Stevenson 1984Stevenson, A. J.

1984 A Diachronic Analysis of Chipped Stone Material from Site 5MT3, Yellow Jacket, Southestern Colorado. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado, Boulder.; Yunker 2001Yunker, Brian

2001 The Yellow Jacket Burials: An Analysis of Burial Assemblages from Two Basketmaker III through Pueblo III Mesa Verde Area Sites. Unpublished MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado, Boulder.). For more detailed information on the regional prehistory and social setting go to Lipe, Varien, and Wilshusen's (1999Lipe, William D., Mark D. Varien, and Richard H. Wilshusen

1999 Colorado Prehistory: A Context for Southern Colorado Drainage Basin. Colorado Council of Professional Archaeologists, Denver.) synthesis of the region's archaeology or Varien's (1999aVarien, Mark D.

1999a Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.) comprehensive examination of the Mesa Verde region's Pueblo II-III communities. Both Crow Canyon (Connolly 1992Connolly, Marjorie R.

1992 The Goodman Point Historic Land-Use Study. In The Sand Canyon Archaeological Project: A Progress Report, edited by W.D. Lipe, pp. 33-44. Occasional Papers, no. 2. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado., 1996Connolly, Marjorie R.

1996 Yellow Jacket Oral History Project, Montezuma County, Colorado. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado. Report submitted to the Colorado Historical Society, Denver.) and the University of Colorado Museum (Lange and others 1988Lange, Frederick , Nancy Mahaney, Joe Ben Wheat, and Mark L. Chenault

1988 Yellow Jacket: A Four Corners Anasazi Ceremonial Site. Second edition. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.) also have produced short summaries of the historic land use in the Yellow Jacket area.

The Local Community

Anthropologists have long recognized that community is one of the most fundamental ways in which households organize themselves to use and reside on local landscapes. A community is made up of a group of households and individuals who typically are in daily contact and who share access to local social and natural resources (see Adler (2002Adler, Michael A.

2002 The Ancestral Pueblo Community as Structure and Strategy. In Seeking the Center Place: Archaeology and Ancient Communities in the Mesa Verde Region, edited by Mark D. Varien and Richard H. Wilshusen, pp. 3-23. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.) and Varien (1999aVarien, Mark D.

1999a Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.) for more detailed discussions). For 5MT1, the size and nature of the community must have changed dramatically between the original occupation of the Stevenson area in the seventh century and the final occupation of the Porter area in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The earlier Basketmaker III occupation of the Stevenson area may have represented one of the larger sites in the Yellow Jacket locality, with its large two large pitstructures and substantial storage rooms. Other than for a possible six pitstructure settlement at Step House (Birkedal 1976:484-489Birkedal, Terge G.

1976 Basketmaker III Residence Units: A Study of the Prehistoric Social

Organization in the Mesa Verde Archaeological District. Unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado,

Boulder.), the largest seventh century settlements in the region consist of hamlets of two pitstructures (e.g., Lancaster and Watson 1954Lancaster, James A. and Don C. Watson

1954 Excavation of Two Late Basketmaker III Pithouses. In Archaeological Excavations in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1950, by J.A. Lancaster, J.M. Pinkley, P. Van Cleave, and D. Watson, pp. 7-22. Archaeological Research Series No. 2. National Park Service, Washington, D.C.; Morris 1991Morris, James N.

1991 Archaeological Excavations on the Hovenweep Laterals. Four Corners Archaeological Project Report 16. Complete Archaeological Service Associates, Cortez, Colorado.; Rohn 1975Rohn, Arthur H.

1975 A Stockaded Basketmaker III Village at Yellow Jacket, Colorado.

Kiva 40(3):113-119.). A slightly earlier Basketmaker III settlement at nearby 5MT3 reinforces the presence of an early occupation of this locality, and it is quite probable that the Yellow Jacket sites were part of a small community. However, since intensive archaeological surveys have not been conducted in the vicinity, it is not possible to fully address community issues for the early occupation.

|

Rubble mound at Yellow Jacket Pueblo, an immense village just to the northeast of the Wheat site complex (SL-YJ-225) |

2003 Artifacts. In The Archaeology of Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Site 5MT5): Excavations at a Large Community Center in Southwestern Colorado [HTML Title]. Available: http://www.crowcanyon.org/yellowjacket. Date of use: December 17, 2004.). At its peak, the population of this single village is estimated to have been between 850 and 1,360 people (Kuckelman 2003bKuckelman, Kristin A.

2003b Population Estimates. In The Archaeology of Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Site 5MT5): Excavations at a Large Community Center in Southwestern Colorado [HTML Title]. Available: http://www.crowcanyon.org/yellowjacket. Date of use: December 17, 2004.), with between 106 and 170 kivas in use. This is at least 30 to 50 times larger than the population of the Porter area, where only one or two kivas were in use at any one time and the estimated maximum population was only 12 to 18 individuals.

Although Yellow Jacket Pueblo must have dominated local community socio-political affairs, it is likely that in day-to-day domestic life the residents of the unnamed roomblock east of the Porter area, of the nearby hamlet at 5MT2 and possibly of the small village of 5MT3 would have had much more influence on the inhabitants of the Porter area. The small hamlet of 5MT2 is so close to 5MT1 (both the Porter area and the unnamed roomblock), that it is quite possible that the households at the two sites shared kinship bonds, held agricultural land in common, or cooperated on various tasks. It is intriguing that there is a one- or two-household pueblo in the Porter area sometime between A.D. 1140 and A.D. 1225, when the earliest component at Site 5MT2 likely consisted of one to two households. In the latest occupations of these two sites at about A.D. 1260, there are potentially two to three households at 5MT2 when there is a single household in the Porter area. It seems likely that these adjacent households must have been tied to one another, but this issue has not yet been addressed in Yellow Jacket research.

Undoubtedly Yellow Jacket Pueblo (5MT5) was the largest and densest residential settlement in the Yellow Jacket community during the late Pueblo II and Pueblo III periods. The presence of public architectural features such as a multistory great house and at least one great kiva leave little doubt that it was the community's center. For the two centuries that Yellow Jacket Pueblo persisted as one of the region's great sites, its estimated catchment area (i.e., the resource area controlled by this community) may have grown from 350 square kilometers to over 2000 square kilometers (Varien 1999a: Tables 7.1-7.3Varien, Mark D.

1999a Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.). It is evident that Yellow Jacket Pueblo must have exercised an immense influence on the occupation and the ultimate abandonment of the Porter area. The nature of the influence of Yellow Jacket Pueblo on a contemporary nearby hamlet such as those at 5MT1 and 5MT2 is a critical research topic.

Natural Resources

There are certain natural resources which are essential to establish and maintain a residential site such as 5MT1. Potable water, agricultural soil, appropriate climate, adequate building materials, abundant wild plant and animal resources, and other specialized items such as potter's clay all are key resources for an ancestral Pueblo settlement in the Mesa Verde region. The Yellow Jacket locality is remarkably well supplied with all these resources, and this in part may have allowed Yellow Jacket Pueblo to have become one of the longest-lived and certainly one of the largest of the Pueblo III villages in the region. The survival of a small hamlet such as the Porter area or 5MT2 certainly must have depended on some sort of pact with or ties to such a large neighboring community center.

Water

|

Standing water in Tatum Draw, a tributary of Yellow Jacket Creek, just east of 5MT3 (SL-YJ-274) |

1996 Yellow Jacket Oral History Project, Montezuma County, Colorado. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado. Report submitted to the Colorado Historical Society, Denver.; Lange et al. 1988:14Lange, Frederick , Nancy Mahaney, Joe Ben Wheat, and Mark L. Chenault

1988 Yellow Jacket: A Four Corners Anasazi Ceremonial Site. Second edition. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.) and likely were as reliable over a thousand years ago. Water must have become an increasingly scarce resource, because by early Pueblo III times at least one large reservoir and a number of smaller water control dams were built at Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Kuckelman 2003cKuckelman, Kristin A.

2003c Subsistence. In The Archaeology of Yellow Jacket Pueblo (Site 5MT5): Excavations at a Large Community Center in Southwestern Colorado [HTML Title]. Available: http://www.crowcanyon.org/yellowjacket. Date of use: December 17, 2004.; Wilshusen, Churchill, and Potter 1997: Table 2Wilshusen, Richard H., Melissa J. Churchill, and James M. Potter

1997 Prehistoric Reservoirs and Water Basins in the Mesa Verde Region: Intensification of Water Collection Strategies during the Great Pueblo Period. American Antiquity 62:664-681.).

Water would have been vital for cooking, drinking, and cleaning, as well as important in building earthen structures, making pottery clay, and possibly even sustaining some crops. Though Yellow Jacket Creek has gone dry in certain seasons during droughty years, it appears that the seeps and even the spring have been dependable throughout historic times. Certainly the early pueblo in the Porter area was well located near water when it was first constructed in the mid- to late eleventh century.

Agricultural Requirements: Soil and Climate

When 5MT1 was first discovered in the 1950s, portions of it were located in a bean field which had recently been put into cultivation. Presently, parts of the site have reverted to sagebrush and grass, with a few young pinyon and juniper trees taking root, while other parts remain under periodic cultivation. The local soils formed in both deep eolian sediment and alluvial sediment along the canyon rims and in the canyon below the site. The soils surrounding 5MT1 are part of the USDA's Cahona-Sharps-Witt soils mapping complex, with the upper horizon consisting of 30 cm or so of reddish brown loam and the subsurface argillic horizon extending to up to 160 cm deep with increasing amounts of calcium carbonate at depth. In the USDA's Soil Taxonomy these soils are fine-silty, mesic Ustollic Haplargids. In everyday language, this means that these soils would have been excellent for prehistoric horticulture, given their ability to hold water, their favorable soil chemistry, their depth, and their gentle slope with a southeast aspect. Nearby fields have been in corn, bean, wheat or alfalfa tillage for in some cases over 80 years, which provides at least anecdotal evidence of the agricultural viability of this area.

|

Fields of cut wheat just to the west of the Joe Ben Wheat site complex (SL-YJ-204) |

1999 Environment. In Colorado Prehistory: A Context for Southern Colorado Drainage Basin, edited by William D. Lipe, Mark D. Varien, and Richard H. Wilshusen, pp. 14-50. Colorado Council of Professional Archaeologists, Denver.). All of these factors make this a relatively promising setting for maize horticulture.

The occupations at 5MT1 date primarily between A.D. 675 and A.D. 700 and between A.D 1060 and A.D. 1280. Overall, these are relatively favorable periods for human habitation of the area, but there are particularly difficult drought periods between A.D. 1130 and A.D. 1180 and between A.D. 1276 and A.D. 1299 (Dean and Van West 2002Dean, Jeffrey S. and Carla R. Van West

2002 Environment-Behavior Relationships in Southwestern Colorado. In Seeking the Center Place: Archaeology and Ancient Communities in the Mesa Verde Region, edited by Mark D. Varien and Richard H. Wilshusen, pp. 81-99. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.). Globally, the Little Ice Age began by A.D. 1250 and brought a period of cooler, drier weather to the Four Corners region. The prolonged drought of A.D. 1276 to A.D. 1299 probably would have caused water tables to fall, which would have exacerbated an already difficult situation.

Although no study has yet been made of the vegetal remains from 5MT1, excavation observations and the preliminary inventory of recovered vegetal remains demonstrate that corn and possibly squash were recovered from both the Basketmaker III occupation of the Stevenson area and Pueblo II and Pueblo III occupations of the Porter area. Because very few flotation samples were taken in the 1950s and 1960s, comparisons between the vegetal remains from the early and late components will primarily show the presence or absence of particular cultivars and ruderal plants. However, there may be sufficient variety and quantity of certain crops such as corn to allow comparisons of the types and morphologies of cultivars grown in the early and later occupations of the site. This might provide one element of a larger comparison of early and late farming strategies in the same locality.

Wild Plants and Animals

Pinyon and juniper cover the canyon rims and talus just south of 5MT1 and, along with the oak, willow, and reeds of the canyons, provided excellent building materials, as well as wood for everything from cradleboards to hoe handles. In addition, various wild berries; ruderal plants such as amaranth; pinyon nuts; some cacti and yucca; as well as various grasses and herbs provided excellent resources for food, basketry, cordage, and medicine. Although the vegetal remains have not yet been analyzed, the preliminary inventory of tentatively identified vegetal materials includes willow twigs, juniper bark and wood, pinyon wood, cheno-am seeds, and beeweed seeds. This list does not represent an expert analysis and does not account for the numerous, as yet unidentified, seeds and plant remains. As with the cultivars, an expert analysis would allow the comparison of the types of plants found in the early and late components. Such an analysis would be important for understanding how land use and agricultural strategies might have changed between A.D. 700 and A.D. 1200 in the Yellow Jacket area.

Rabbits, mule deer, elk, and semi-domesticated turkey all would have been possible sources of meat, bones for tools, and other household products. A very limited examination of the faunal materials includes the following species: badger, cottontail, prairie dog, turkey, marmot, chipmunk, jack rabbit, squirrel, bighorn sheep, and mule deer. This list is not exhaustive, nor does it represent an expert analysis of the majority of the items in the collection. Many of the faunal items in the 5MT1 collection were not collected by screening, but even with that limitation, the sheer size of the collection and temporal range represented by the materials should allow for some important analyses, especially when combined with larger-scale regional studies (e.g., Driver 2002Driver, Jonathan C.

2002 Faunal Variation and Change in the Northern San Juan Region. In Seeking the Center Place: Archaeology and Ancient Communities in the Mesa Verde Region, edited by Mark D. Varien and Richard H. Wilshusen, pp. 143-160. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.). A number of pieces of animal bone were fashioned into hide-working or weaving tools.

Geologic Resources

|

Yellow Jacket Canyon just south of 5MT3, near location of possible clay mines (SL-YJ-194) |

There also are nearby clay deposits on the talus slope of Yellow Jacket Canyon, just southeast of 5MT1 and south of 5MT3. These clays are suitable for ceramic production (Lange et al. 1988:19Lange, Frederick , Nancy Mahaney, Joe Ben Wheat, and Mark L. Chenault

1988 Yellow Jacket: A Four Corners Anasazi Ceremonial Site. Second edition. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.) and the raw clays, ceramic production tools, and pottery kilns found at the Yellow Jacket sites lend credence to the idea that much of the pottery at the sites was produced locally. A recent study (Mobley-Tanaka 2005Mobley-Tanaka, Jeanette L.

2005 Community from Within: Intracommunity Interaction and the Social

Formulation of the Yellow Jacket Community, Southwest Colorado, A.D.

1200-1300. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University, Tempe.) supports this proposition and compares pottery production and distribution at these smaller settlements to those at the larger nearby village.

Finally, it is likely that many of the raw materials for the numerous chipped stone tools, pendants, and ground stone implements are locally available, but more detailed analytical studies are needed to confirm this.

Historic Disturbance

Aerial photos of this area taken in 1940 (CDL 43-49 and 43-50) show that 5MT1 was covered at that time by brush and small trees. There are large fields about one mile to the north, but the slightly rougher and sloping terrain close to the canyon probably was less favorable for mechanical cultivation. By 1953, when Joe Ben Wheat first heard about the Yellow Jacket sites, the land around 5MT1, 5MT2, and 5MT3 was being cleared for cultivation. It appears that the landowner, H.B. "Hod" Stevenson, had excavated either in these sites or at other nearby Yellow Jacket sites prior to that time. Based on a note with one of the two groups of pots he donated to the Museum, it appears that about two thirds of the approximately 50 whole vessels in the donation came from sites on his Yellow Jacket land.

|

Pinto bean fields and Site 5MT1 in the late 1950s (SL-YJ-039) |

1992 The Goodman Point Historic Land-Use Study. In The Sand Canyon Archaeological Project: A Progress Report, edited by W.D. Lipe, pp. 33-44. Occasional Papers, no. 2. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.). Regular plowing of the area began by at least 1953 and Joe Ben Wheat's pictures of the Stevenson area in 1954 show totally cleared field areas in pinto bean cultivation. This kind of clearing and cultivation heavily disturbs the upper 20 to 25 centimeters of soil and typically accelerates erosion in a situation such as in the Stevenson area of the site, where the slope angle is about 5 to 8 percent dipping to the south and east.

In contrast with the Stevenson area, it appears that the Porter area was not regularly cultivated because of the danger the stone in the roomblocks presented to Stevenson's farm equipment. Portions of the western edge of the Pueblo II and Pueblo III occupation were plowed, particularly Kiva E and Subterranean Room 14, but the remainder appears never to have been plowed. The unnamed roomblock located east of the Porter area, which is clearly visible in the aerial photographs, also was not plowed. By the late 1960s this area had begun to revert to sagebrush and small pinyon and juniper trees. The Stevenson area was cultivated through the 1980s and showed evidence of at least intermittent plowing as late as the fall of 2004.

Setting

Setting